This is the third of a series of articles, which contain parts of my book, Becoming a Bedside Advocate: Insight and Information to Help Your Loved One Through the Modern Healthcare Experience.

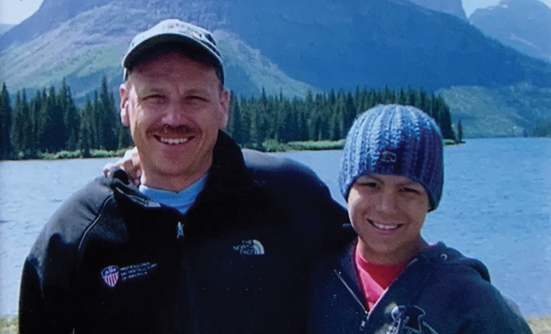

My husband Rick had been diagnosed with stage IIIA distal esophageal adenocarcinoma in 2017. On December 11, 2018, while hospitalized at Savannah Memorial Hospital, Rick was very ill, and his critical care physician phoned me around 1 AM to come right away. They couldn’t say how much time he had.

Wild Horses

I drove the back roads from our home in Palmetto Bluff to Savannah. The night was pitch black, and my high beams hardly pierced the darkness. I didn’t know how long Rick could hold on. Straining to focus on the road, I remembered whispering to Rick months earlier, “Wild horses couldn’t drag me away from you.”

When I arrived at the hospital, Rick’s eyes were closed, but he was pulling at his hospital gown, struggling. I placed his hands on my body to comfort him, and I quietly said, “Rick, I’m here. I’m here, my sweetheart.”

He had respiratory failure, the doctors said, and we agreed that a ventilator was not only inhumane but also against Rick’s wishes, as expressed in his healthcare directives. To help him breathe, they suggested a BiPAP (which is a mask, not intubation) and I agreed, so he could get some oxygen. It was too much to see him struggle. He was moved to another room later that night.

I called our daughter Kelly and her husband Stephen in Raleigh at 3 AM. It was time for everyone to come to Rick’s bedside. They called the other children and Rick’s lifelong friends while driving the 5 hours from Raleigh to the hospital.

Denial

By morning, Kelly and I were in his room. He was skeletal but awake, eating a popsicle. His eyes were clear. He would fall asleep for several minutes and would occasionally call out for me. He was not in pain. His physicians offered no indication as to how close Rick might be to death. We were in denial anyway.

Seeing our once-strong, kind Rick starving and emaciated, became too much for our sorrowful hearts. Desperate, I asked Dr. Gard, our hospitalist, if Rick could have a feeding tube like he’d had after his surgery, hoping it would help him overcome this setback. The doctors gathered to explain why that would do more harm than good. Still, none of the doctors said he was dying.

Nobody mentioned that we could have people from hospice come speak with our family, and I didn’t know enough to ask for a hospice representative. Again, he had a BiPAP mask at night to keep him alive.

The next morning, Kelly, Stephen, and Rick’s granddaughter Sarah, all in their 20s, arrived. Rick was awake and engaging. Kelly said, “He looked and acted a hundred years old,” but he spent 45 minutes chatting with his millennials, teasing and being himself. He’d fought his way through the night to have this time with them. It was his gift.

When I arrived with our older daughter, Carolyn, Rick was losing energy and could barely be heard. He greeted me with a soft, “I love you,” followed by, “Where’s Carolyn?” She took his hand, and they had their private moments together. Rick had raised Carolyn, my daughter from a previous marriage, since she was 5. He loved her as his own, and she loved him.

I retrieved his wedding band from my bag. “I’d better put this on your finger to let everyone know you’re taken,” I told him as I slipped it onto his ring finger. It was much too big for him now. He closed his eyes, very weak, but he was still listening.

Know When to Say “No”

Dr. Gard came into the room. We were all there. Dr. Gard stood at the foot of Rick’s bed and told us he thought we should now move into hospice service.

I leaned over to Rick and asked, “Do you want any more treatment? More oxygen treatment?” “No!” he called out as loudly as his shadow could.

I turned back to Dr. Gard. “There you have it. Rick doesn’t want more treatment, and I have his healthcare directives. So, we all agree to go into hospice.”

Dr. Gard stood there looking at all of us and began to weep. We were all touched, having never seen a physician weep like this before. Later I asked Dr. Gard why he had been moved to tears. He explained that it was a combination of things, but mostly he was touched by all the young adults in the room who were there for Rick.

Follow the Patient’s Wishes

It was unusual, he explained, for a family to lovingly move into hospice, all in agreement and supportive of the patient’s best interest. He said that too often, patients have no one by their bedside, or have family members who put their own wishes ahead of the patient’s. He was saddened that he couldn’t help Rick overcome the setback and live longer.

“You were good advocates,” Dr. Gard said, and then added, “I probably would have really liked Rick.” And there it was—the “white coat,” the “boots on the ground,” revealed as a hardworking, compassionate healer and a wonderful human being. A hero.

A Catholic priest was called to give the Last Rites. The hospice nurses advised us to go home, sleep for a few hours, and come back in the morning. The process could take several days, we were told.

We arrived as a group early the next morning, on December 13. Rick’s lifelong friends, Tom and Joy Jackson, arrived an hour or so later.

Rick had a pain medication patch and looked to be sound asleep. His breathing was very shallow: he was lingering for us. The doctor told us Rick could hear us. Hearing is the last sense to go, he said. A hospital chaplain guided us in our last words to Rick.

We all stood around Rick’s bed touching him and even, for a moment, chatting as if we were gathered in our kitchen. The millennials tuned in an iPhone to Rick’s favorite music, the Eagles and Motown.

Tom and Joy, lifelong friends, were the first to say their private goodbyes to Rick, then left us. We thank God for their friendship. Zack and Kim Taylor, our son-in-law Stephen’s parents, sent a beautiful letter, which Stephen read aloud to Rick. Rick’s estranged daughter from a previous marriage, Kari, texted a message of love, which I read to him. He heard every word.

As we prepared for what was to come, each of Rick’s loved ones in the room stood close to him, touching him and saying their goodbyes. Love, gratitude, forgiveness.

Kelly said to her father, “It’s okay to go to Heaven, Dad. We’re going to be okay.” Then at last came my turn. I held Rick and spoke softly.

“Love of my life, you’ve provided for my every desire, family, friendship, home, a wonderful life....I love you. Please forgive me if I’ve ever hurt you. Now it’s time for you to go to Heaven. We’ll take care of one another.”

As I spoke, we watched Rick’s spirit leave his body until the physical shell that remained didn’t even resemble the man we knew. The room was full of supernatural love and forgiveness. We were sad and happy at the same time. Rick was no longer suffering.

Hospice Care

We all did our absolute best as advocates for Rick. But I can’t help thinking that perhaps if we had engaged hospice sooner, we might have had more time to be together in peace, especially considering the endless emergency room visits, each involving 6 to 12 hours waiting to be seen, or Rick ending up hospitalized for a few days but never really getting better, only to have to go back to the emergency room every week or so.

In a conversation with Sandra Bond, then the Executive Director of Compassus in South Carolina, I learned about how hospice works. Hospice care is a continuation of the medical care, just like physical care or speech therapy. Hospice care is about quality of life instead of quantity of life.

Hospice will forego all curative measures to allow the patient to have quality of life until dying a natural death from the disease process. Treatment during hospice is meant to manage symptoms, such as relieving pain, not to cure the disease (which is no longer curable).

After his initial battle to recover from surgery, one afternoon Rick was able to do what he had longed for—to take his victory walk to the dock, sit with me, and just enjoy the peaceful May River off Palmetto Bluff.

But there will be a time when fighting becomes all-consuming and a cruel, losing battle. Hard as it is to admit, we ultimately cannot beat death. That’s where hospice comes in.

According to Ms. Bond, people often wait too long for hospice care, likely because we don’t truly understand what hospice is, and the services hospice can provide to patients and their caregiver or caregivers.

Hospice requires patients to meet eligibility criteria to enter hospice care. The criteria are determined by the hospice. You must ask for a referral to hospice.

Like our family, many people don’t think about hospice as an alternative to active treatment, especially while they’re fighting.

A Good Advocate

Doctors will do everything possible to keep their patients alive and heal them, but they’ll wait until the very last minute to mention hospice. So, like everything else, the advocate has to ask for hospice.

Ask for a hospice representative to come talk with you and your loved one. The conversation does not mean you’re ready to give up the fight at that moment. It means that you will understand your options when the time comes.

It may take a little courage to ask about hospice. I wish I’d known enough to ask. Rick was about 24 hours in hospice before he died. Maybe his suffering could have been eased had we gone into hospice care earlier; it’s hard to know. But it’s good to consider all the options, including hospice.

I asked Ms. Bond, “What do you want the advocate to know?” Here is her paraphrased answer:

- Learn as much as possible about the disease your loved one has. Try to find out what to expect in terms of recovery and disease progression.

- Advocate to discharge planners. Again, this is very important from a hospice perspective. Discharge planners will take the path of least resistance in discharging patients from the hospital. Their job is to find a place that you want to be. Hospice is an option, but it requires more time and effort from the discharge planner. You’ll have to ask for it. Request to talk with a hospice provider. Advocate for the service you want for your loved one.

- There are 4 levels of hospice care: routine home care, respite care in a certified Medicare facility, continuous home care, and general inpatient care provided in a hospital setting. All 4 levels are offered by every hospice agency, and each level of care must be determined by the medical team. Check with your hospice agency what contractual relationship they may have with local facilities. Check with your insurance company about your healthcare and long-term care insurance coverage.