The topic of health disparities has gained considerable attention over the past 2 years. Many populations, especially Black and Hispanic communities, encounter barriers to care and may receive lower quality or different services than white patients when dealing with a cancer diagnosis.

As a Black woman and a breast cancer surgeon, I see these inequities and struggles firsthand, especially related to triple-negative breast cancer, or TNBC.

Understanding Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Some women don’t realize that there are different types of breast cancer, and many have never heard of TNBC. The type of breast cancer and the characteristics of the cancer cells help to determine the stage of cancer, the treatment options, and your chance of becoming cancer-free. Treatment may include surgery, chemotherapy, oral medications, and radiation aimed at eliminating the spread of cancer. TNBC is very aggressive and has fewer options to treat and prevent recurrence than other types of breast cancer.

Although Black and Hispanic women, carriers of the BRCA mutation, and younger women are at increased risk for TNBC, women of color are often not referred for early or appropriate imaging, because of knowledge gaps in the medical and lay communities. Delays and limited access to screening because of the pandemic have further exacerbated the situation. Consequently, these women often have poorer outcomes and higher mortality, which is unacceptable and preventable.

Before we can implement changes, we need patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers to have a better understanding of TNBC and the significant impact it has on Black and Hispanic communities.

Let’s start with the basics. Overall, 1 in 8 women will have breast cancer in her lifetime.1 In 2022, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer are expected to be diagnosed in the United States,2 and up to 20% of those cases will be TNBC.3 The signs and symptoms of TNBC are similar to other types of breast cancer and may include having a palpable mass, visible dimple, breast swelling, nipple retraction, crusting or discharge, breast skin that is red or thickened (this “redness” may appear more subtle in women of color), and swollen lymph nodes under the arm or near the collarbone. Most common is having no symptoms at all, which makes early detection especially important.

Biologically, TNBC is different from other forms of breast cancer: its tumor cells lack 3 key receptors—estrogen, progesterone, and HER2—that current therapies target in other types of breast cancers. Therefore, the treatment options for TNBC are limited, and no single oral drug is available to prevent its recurrence.

TNBC is an aggressive cancer, is often diagnosed at later stages, and has a higher chance of becoming metastatic (spreading to other parts of the body) than other types of breast cancers.

Which Women Are at Highest Risk for TNBC?

Although any woman can have TNBC, this type of breast cancer disproportionately affects Black, Hispanic, and younger women.4

- Black women are almost 3 times more likely to be diagnosed with TNBC than non-Hispanic white women,5 and they have the lowest survival rate, by the stage of diagnosis, of any racial or ethnic group.6

- Black women have up to 31% increased breast density, limiting the sensitivity of mammography to detect masses in these women.7

- Hispanic women are also diagnosed with TNBC more often than white women and are at a higher risk of death from TNBC.8

- Women under age 40 are diagnosed with TNBC nearly twice as often as older women.4 Most other forms of breast cancer occur in middle-aged or older women.1

- Obesity can increase the risk for TNBC, and obese premenopausal women have a 42% greater risk of being diagnosed with TNBC compared with non-obese premenopausal women.9

Healthcare Providers’ Lack of Knowledge

Despite research indicating which women are most at risk for TNBC, there is often a disconnect in how physicians care for their Black or Hispanic patients. To change this, physicians must be better educated about TNBC risk factors and listen to, evaluate, and screen Black and Hispanic women sooner rather than later.

In addition, current mammogram guidelines do not place enough emphasis on initiating screenings earlier for Black and Hispanic women, who are at elevated risk for TNBC. Detailed family history and genetic testing for hereditary mutations also need to be considered. Notably, the BRCA1 gene mutation is more common in TNBC than the BRCA2 mutation,10 and despite similar rates of mutation, women of color are not tested with the same frequency as white women.11

If a 30-year-old Black woman goes to her doctor for breast abnormalities, there is a good chance that she will not be sent for a mammogram or for further testing, because of her doctor’s lack of recognition of TNBC risk factors. As a result, Black women often have larger TNBC tumors than white women at diagnosis and are diagnosed at a later stage, when treatment is less likely to be effective.12

Studies have shown that when women don’t pay attention to changes in their breasts, and when physicians are not aware of TNBC risk factors and the treatment protocols, these harmful consequences occur:

- Black women have a 38% increased risk of being diagnosed with stage IV (metastatic) TNBC compared with white women.13

- Delays in initiating treatment after receiving a TNBC diagnosis are significantly longer in Black than in white women.14

- Black women are 48% less likely than white women to receive guideline-based care for TNBC.13

- Black women are more than 30% more likely to die from TNBC than white women.12

Implementing Change to Save Lives

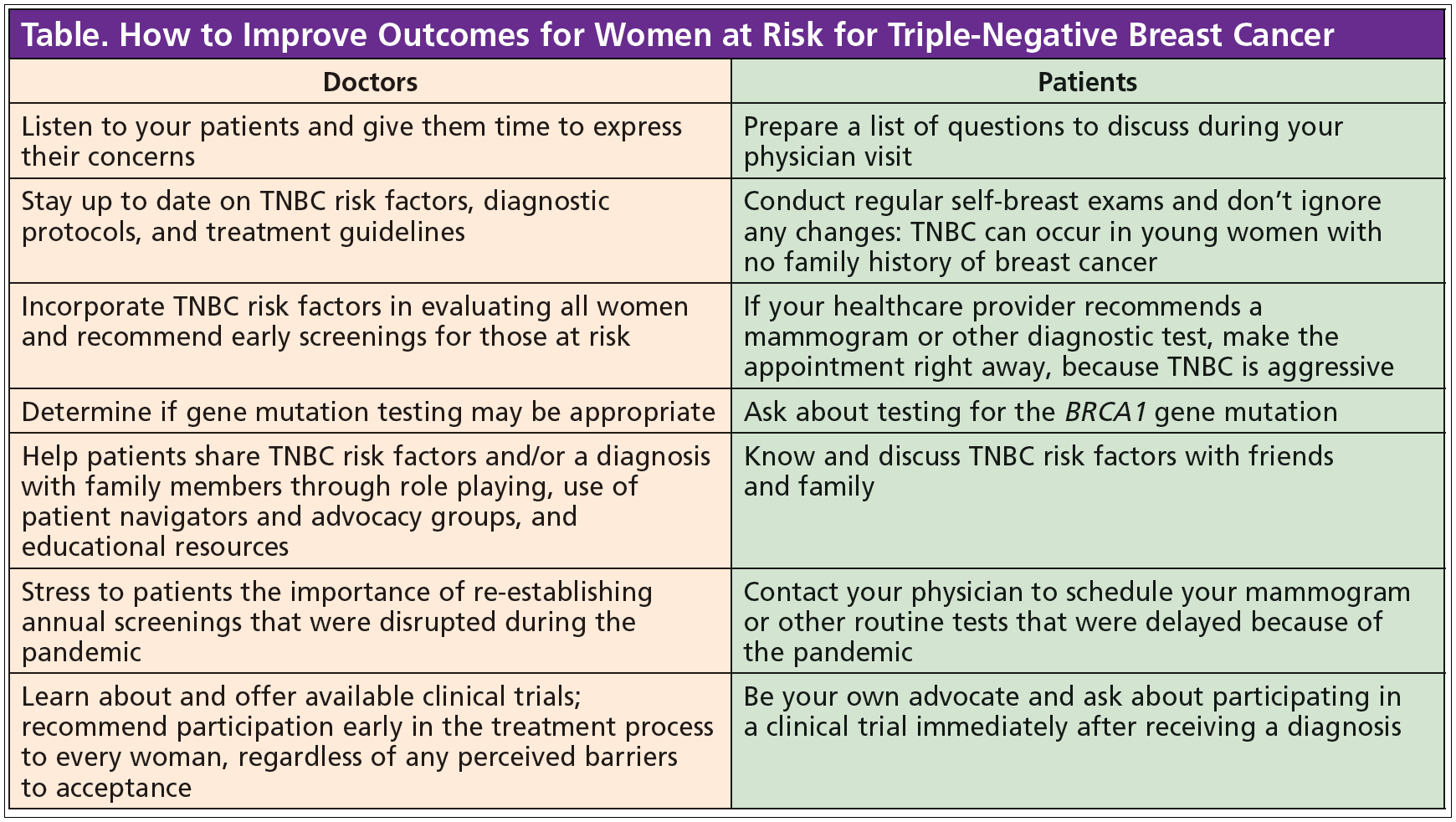

Physicians must listen to the concerns of their patients and provide individualized care by referring women, regardless of their age or family history of breast cancer, for appropriate screening and/or diagnostic tests to rule out TNBC. The Table (see below) lists actions that healthcare providers and patients can take to improve outcomes for women at risk for TNBC.

TNBC may be difficult to detect on a mammogram, because it may lack the most suspicious features seen on mammography, such as irregular mass shape, spiculated margins, and associated calcifications.15 MRI screening more accurately detects abnormalities associated with TNBC15 and has significant value in evaluating breast problems in Black and Hispanic women.

White women with a low (less than 20%) risk of breast cancer are 62% more likely than Black or Hispanic women to have an MRI for breast abnormalities.16 This additional test is often not made available to Black and Hispanic women.

To improve the chances of early diagnosis and survival for patients with TNBC, we need to raise awareness among Black and Hispanic women of all ages, premenopausal women, as well as their families and medical providers. Furthermore, we know that Black women are represented in less than 3% of breast cancer clinical trials.17 This is indefensible.

Representation matters, and we must advance the science to understand and treat more effectively those who are disproportionately dying of this disease. It is time for us to practice what we know, on every level.

I firmly believe that every person, including patients, caregivers, friends, nurses, and physicians, has a role to play in improving the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of TNBC so these women can live longer, healthier lives as survivors and thrivers.

References

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Breast Cancer: How Common is Breast Cancer? Updated January 12, 2022. https://bit.ly/3rrLC6U.

- Breastcancer.org. Breast Cancer Facts and Statistics. Updated July 14, 2022. https://bit.ly/3BWMKnG.

- Kumar P, Aggarwal R. An overview of triple-negative breast cancer. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2016;293(2):247-269. https://bit.ly/3EaqB8n.

- Plasilova ML, Hayse B, Killelea BK, et al. Features of triple-negative breast cancer: analysis of 38,813 cases from the National Cancer Database. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(35):e4614. https://bit.ly/3fDYX9j.

- McCarthy AM, Friebel-Klingner T, Ehsan S, et al. Relationship of established risk factors with breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Medicine. 2021;10(18):6456-6467. https://bit.ly/3C6l2oP.

- DePolo J. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Deadlier for Black Women, Partially Due to Lower Surgery, Chemotherapy Rates. Breastcancer.org. Updated February 22, 2022. https://bit.ly/3UWpGy6.

- Friebel-Klingner TM, Ehsan S, Conant EF, et al. Risk factors for breast cancer subtypes among Black women undergoing screening mammography. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2021;189(3):827-835. https://bit.ly/3Ct7WU1.

- Wang F, Zheng W, Bailey CE, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in all-cause mortality among patients diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2021;81(4):1163-1170. https://bit.ly/3yb2v9s.

- Pierobon M, Frankenfeld CL. Obesity as a risk factor for triple-negative breast cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;137(1):307-314. https://bit.ly/3V1AFGS.

- Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(26):4282-4288. https://bit.ly/3SUpRZg.

- Reid S, Cadiz S, Pal T. Disparities in genetic testing and care among Black women with hereditary breast cancer. Current Breast Cancer Reports. 2020;12(3):125-131. https://bit.ly/3UYBekI.

- Cho B, Han Y, Lian M, et al. Evaluation of racial/ethnic differences in treatment and mortality among women with triple-negative breast cancer. JAMA Oncology. 2021;7(7):1016-1023. https://bit.ly/3SOuLqu.

- Chen L, Li CI. Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2015;24(11):1666-1672. https://bit.ly/3M5QLuL.

- Thomas K, Shiao J, Rao R, et al. Constructing a clinicopathologic prognostic model for triple-negative breast cancer. American Journal of Hematology/Oncology. 2017;13(1):11-21. https://bit.ly/3dZegZU.

- Dogan BE, Turnbull LW. Imaging of triple-negative breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(suppl 6):vi23-vi29. https://bit.ly/3Cu0FDk.

- Haas JS, Hill DA, Wellman RD, et al. Disparities in the use of screening magnetic resonance imaging of the breast in community practice by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Cancer. 2016;122(4):611-617. https://bit.ly/3e2zztu.

- Al Hadidi S, Mims M, Miller-Chism CN, Kamble R. Participation of African American persons in clinical trials supporting U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of cancer drugs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173(4):320-322. https://bit.ly/3Ecnf4F.