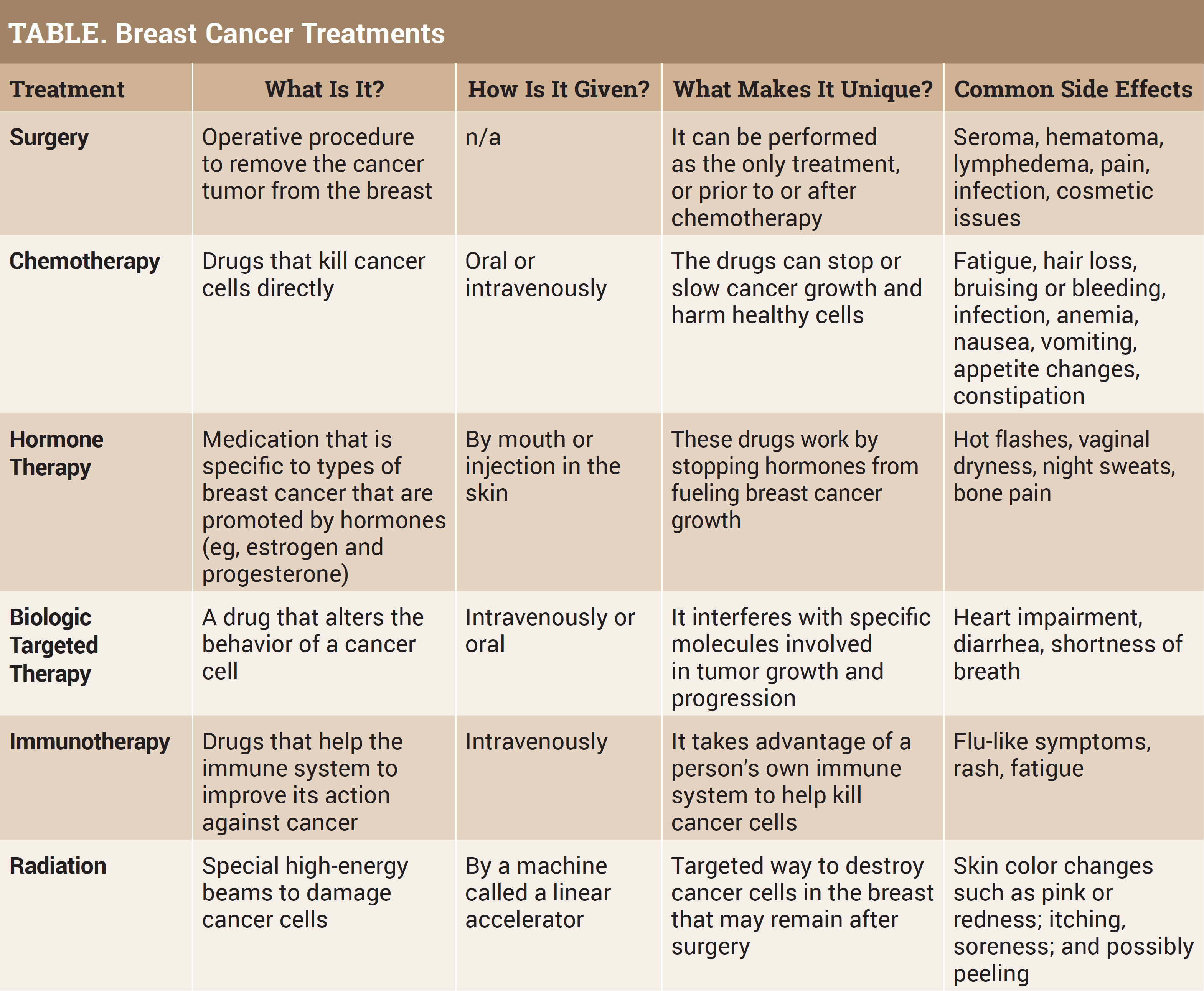

Breast cancer treatments are different for each patient, but the main goals are to eliminate the body of cancer and prevent the disease from coming back. The treatment choice your physician will discuss depends on the breast cancer type; size; if the cancer has spread in your body (stage); receptor features such as estrogen, progesterone, and HER2; menopause status; other health conditions; and most importantly your personal preference. With different choices and the patient’s role in shared decision-making, it is ideal to learn about treatment options.

Surgery

A standard of breast cancer treatment continues to be surgery, whether it is to remove breast tissue, reconstruct a breast, or implant a device such as a port-a-cath to allow easy access to a patient’s veins for prescribed treatment. Breast cancer surgery may be used alone or in combination with other treatments, such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, and radiation therapy. The surgeon is a member of the multidisciplinary breast team and will help decision-making around the type of breast surgery (lumpectomy, mastectomy), immediate or delayed reconstruction (implant or use a patient’s body tissue from another area), or the use of chemotherapy prior to surgery (neoadjuvant therapy).

Breast surgery is performed by a surgeon who is especially skilled in operating on the breast. Breast reconstruction is performed by a breast oncology surgeon or plastic surgeon. Surgeons trained in both of these specialties are known as oncoplastic surgeons. Oncoplastic breast surgery improves cosmetic outcomes by using reconstructive surgical techniques to shape the remaining breast after removing tissue or forming a new breast following excision of breast tissue. Many women use oncoplastic surgery to correct the unevenness between the breasts.

When a surgeon says that all the cancer was removed, the understanding of this statement may be different between a surgeon and a patient. The surgeon did get all the cancer that was visible on a mammogram or breast MRI, but the patient and family may interpret this to mean that there is no longer any cancer in the body, and that no further treatment is needed. This interpretation can be true for a small number of very early, low-risk breast cancer types, but one can still have cancer cells somewhere in the body. The bottom line is that patients will need to continue follow-up with the other interdisciplinary team members to discuss any further treatment to prevent the cancer from returning.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy may be given in a neoadjuvant approach (before surgery) to shrink the cancer so it can be removed with less extensive surgery. This method treats cancers that are too big to be removed by surgery when first diagnosed, and it also allows the medical oncologist to see how the cancer responds to the drugs. The goal is to reduce the cancer in the breast as well as lower the risk of the breast cancer coming back. Also, chemotherapy after surgery (called adjuvant treatment) is administered to kill any cancer cells that might have been left behind or have spread and were not detected on imaging. The goal remains to lower the risk of the breast cancer coming back.

The medical oncologist will choose, prescribe, and order administration of chemotherapy if this treatment is required. Think of the medical oncologist as a quarterback calling the plays, and the other players on the team are the surgeon, the radiologist, the radiation oncologist, and the pathologist for decision-making regarding the best treatment options. The medical oncologist has a clear understanding of the risk of recurrence with a particular type of breast cancer, as well as the overall prognosis, and will share this with the patient, who is also a team member in shared decision-making. If needed, this physician may also prescribe hormone therapy, biologically targeted therapy, or immunotherapy to treat the breast cancer.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy is also called endocrine therapy. When a breast cancer is diagnosed, the pathologist tests for hormone receptors called estrogen or progesterone. If the receptors are detected, the cancer has an identifiable trait as estrogen positive or progesterone positive (ER+; PR+). Approximately 80% of breast cancers are positive, and this group will qualify for hormone therapy. The cancers that are hormone negative do not have hormone receptors and will not respond to hormone therapy. Estrogen and progesterone bind to hormone receptors and cause the receptors to become active and stimulate cell growth. Hormone therapy prescribed by the medical oncologist stops the growth of hormone-sensitive tumors by blocking the body’s ability to produce hormones or by interfering with the effects of hormones on breast cancer cells.

Hormone therapy for breast cancer should not be confused with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or menopause hormone therapy—treatment with estrogen alone or in combination with progesterone to help relieve symptoms of menopause. For this reason, when a woman taking HRT is diagnosed with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) breast cancer, she is usually asked to stop that therapy. There are 2 different types of therapy that create opposite effects: hormone therapy for breast cancer blocks the growth of HR+ breast cancer, whereas HRT can promote the growth of HR+ breast cancer.

Also, many patients think of hormone therapy as being less powerful than chemotherapy, but it can be just as effective in certain breast cancers. Both hormone therapy and chemotherapy are considered “systemic” therapies because they travel throughout the body and through all the body systems. Surgery and radiation therapy are considered “local” treatments because they focus on 1 body part.

Biologic Targeted Therapy

Biologic targeted therapy can also be called molecularly targeted drugs, molecularly targeted therapies, or precision medicine. Just as hormone therapy is used for breast cancer cells with a specific characteristic or trait, biologic targeted therapy is also used in this manner. Again, the pathologist measures the specific levels of a protein in cancer cells and compares them with levels from healthy cells. Overproduction of these proteins are found in greater amounts in cancer cells but not in healthy ones, and the large amounts contribute to cell growth. The purpose of the targeted therapy is to tackle and attack these proteins and disable their function by blocking the cancer cells’ ability to receive growth signals. Targeted drugs work differently from chemotherapy drugs. Chemotherapy can kill the normal cells when eliminating the cancer cells, which causes side effects such as hair loss and low blood counts, whereas normal cells can survive the targeted therapy. The most common abnormal protein in breast cancer is a growth-promoting protein known as HER2, which is found in 20% of all breast cancers. Some drugs that target this protein are Herceptin, Perjeta, Kadcyla, Enhertu, Tykerb, and Nerlynx. Only breast cancer patients who have a high level of this protein will be prescribed one of these medications by the medical oncologist.

Immunotherapy

Normally, the immune system detects and destroys abnormal cells and prevents or slows the growth of cancers. Sometimes, immune cells called tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are found around cancers, and this is a sign that the immune system is responding to something that does not belong in the body. Unfortunately, cancer cells have ways to avoid being destroyed by the immune system. Immune checkpoints are a normal part of the immune system. The immune response does not need to be so strong that it destroys healthy cells in the body, so there are immune checkpoints that are a normal part of the immune system. Breast cancer cells sometimes use these checkpoints to hide and cut off the immune system so they will not be destroyed. But immunotherapy drugs can target these checkpoints and restore or cut back on the immune function. Tecentriq is used in breast cancer treatment to help boost the immune response to shrink or slow breast cancer growth.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is planned by a radiation oncologist in conjunction with women with breast cancer who need it. It can be administered after a lumpectomy or a mastectomy, or as palliative treatment if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. Two main types of radiation therapy are used to treat breast cancer: (1) external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), given from the outside and aimed at the breast tissue, and (2) brachytherapy, in which a device is placed into the breast tissue in the area where the cancer was removed. With EBRT, the whole breast may be treated for approximately 6 weeks—once a day Monday through Friday—or it may be treated in a hypofractionated way with larger doses given over 3 to 4 weeks. In some centers, accelerated partial breast irradiation has been used in which larger radiation doses are given over a shorter time to only part of the breast, not the entire breast.

Radiation therapy will not cause the patient to be radioactive. The radiation will be given to the breast tissue in a few minutes. There is no lingering radiation once the treatment machine is turned off. If brachytherapy or internal radiation is received, the person will be radioactive while the material is implanted and may be secluded in the hospital in a private room.

Physicians associated with each treatment may discuss clinical trials in which patients volunteer to participate in testing new drugs therapies, devices, interventions, screening methods, or diagnostic tests to prevent, diagnose, treat, or manage cancer. The treating physician will have all the latest information, and resources such as navigators, research staff, and local or national patient advocacy organizations are there for anyone who has an interest in a clinical trial. No matter what type of clinical trial a patient may be offered, they can feel reassured that the drug, device, etc, has already gone through extensive testing in the laboratory, and usually also with other patients, prior to it being offered as a treatment option now. Patients are followed very closely. They will be receiving the current standard of care or what is hoped to become the new standard of care for the type of cancer they have.

Patients often say, “I had no idea until I was diagnosed how many types of breast cancer there are, nor did I know anything about the different types of treatment.” They speak with friends or colleagues who have undergone breast cancer treatment and realize that each person had a different treatment plan. The patient is a vital part of the shared decision-making process around treatment plans, and asking clarifying questions is a vital tool in understanding care. If additional resources are needed for understanding standard of care, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Society of Clinical Oncology are respected organizations that regularly review and update their guidelines in cancer care.

Patient Resources

Susan G. Komen

www.komen.org

Chemocare.com

www.chemocare.com

American Cancer Society

www.cancer.org

National Cancer Institute

www.cancer.gov

Breastcancer.org

www.breastcancer.org