Genetics is the study of genes. Genetic testing can be extremely helpful to discover an increased risk for developing certain types of cancer in patients and their families. Our genes provide our cells with the instructions for normal cell growth and development. An error in a gene is called a mutation. Cancer cells occur when cells mutate and are not able to function normally. According to Suzanne M. Mahon, DNSc, “One of the most important things you can do to potentially reduce the chance of developing cancer is to know your family history and seek risk assessment and genetic counseling if many cases of cancer exist in your family.”1 Genetic testing can have implications for the whole family.

What Happens When There Is a Gene Mutation?

Somatic mutations, or “acquired” mutations, are the most common cause of cancer. Somatic mutations are acquired during a person’s lifetime, usually by an event or substance referred to as a carcinogen. A carcinogen is an agent known to cause cancer, such as tobacco and certain toxic chemicals.

Germline, or “inherited,” mutations are passed directly from a parent to a child. As it relates to cancer, specific inherited traits or genes can increase the likelihood that the individual will develop cancer. Only about 10% of all cancers are inherited. Each person is born with 2 copies of a particular gene, 1 from each parent. If the person inherits a mutated gene from either parent, he or she still has 1 normal copy. This does not necessarily mean the person will develop cancer, but the potential is higher due to having the mutation.

For example, a common genetic test, BRACAnalysis, is used to detect specific mutations that can drive the development of breast and ovarian cancer. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are tumor suppressor genes. Being born with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations increases the risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer.2

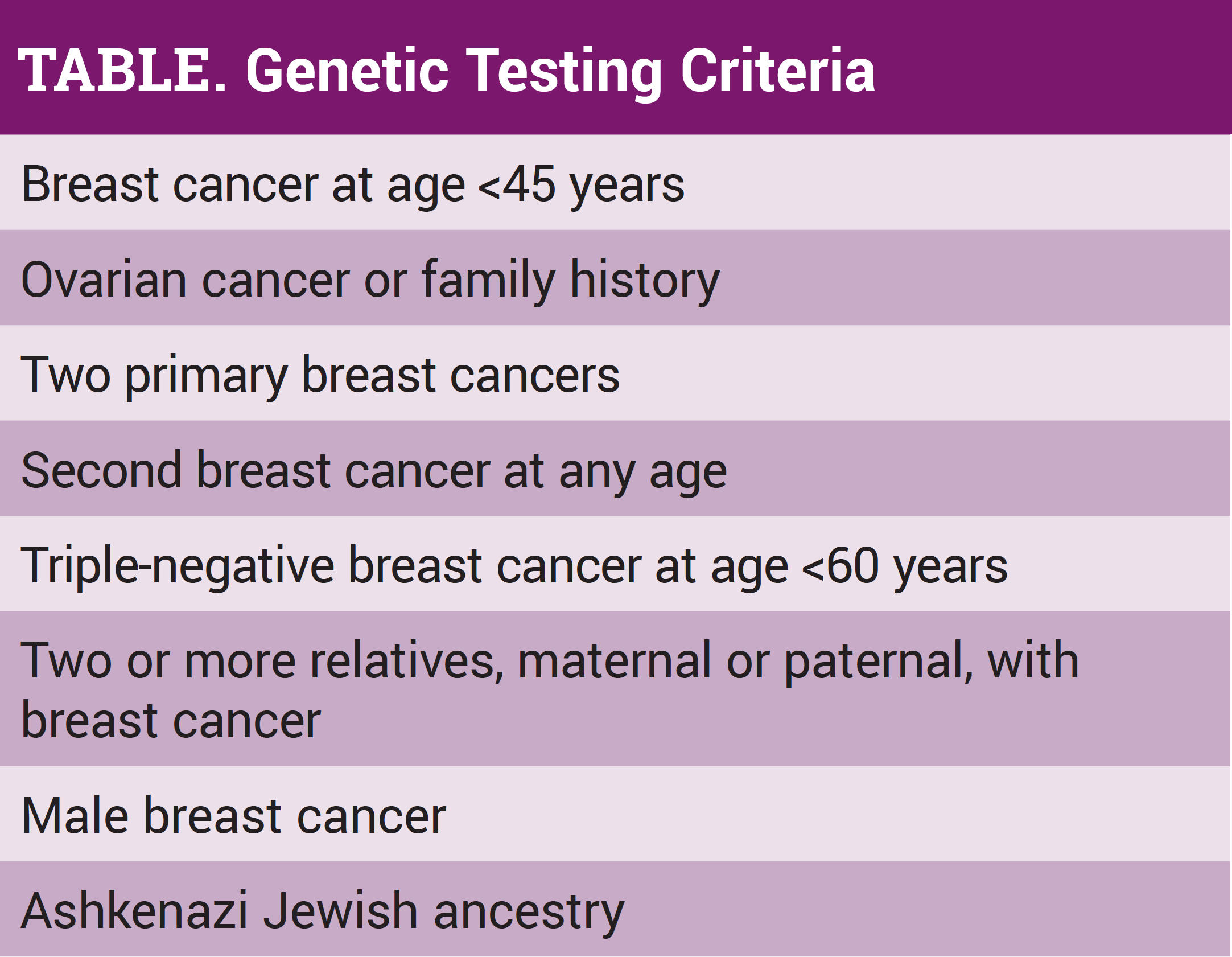

Genetic testing detects inherited mutations that are linked to cancer development. This often includes BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, PALB2, PTEN, and TP53. (See Table. Refer to National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hereditary Cancer Testing Criteria for High-penetrance Breast and/or Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Genes. Version 1.2020).3 This is important because a genetic mutation no longer only applies to breast and gynecologic cancers.

What Is the Process?

The potential benefits, limitations, and risks of genetic testing, as well as the emotional readiness of the person, should be discussed with a healthcare practitioner (HCP) prior to offering genetic testing. In the past, genetic testing focused on 1 or 2 genes. However, the introduction of multigene testing for hereditary forms of cancer has changed the landscape for the testing of at-risk patients and their families. These tests simultaneously analyze a set of genes associated with a certain disorder. Multigene testing is more cost-effective and increases the likelihood that a gene variant will be discovered. It is a good idea to check with specific insurance companies to determine coverage prior to having any genetic testing performed. Many plans, like Medicare, have very specific rules about testing.

HCPs will ask patients to complete a questionnaire that provides details about family medical history to include first- and second-degree relatives on both the maternal and paternal sides. It needs to be as detailed and accurate as possible. The HCP will use a diagram called a pedigree to map out the family history. A blood or saliva sample will be required for testing, and the results will be available in 2 to 3 weeks. This information will help determine whether there is a need for further testing.

Genetic professionals recommend that the individual stay in touch at regular intervals to see if more testing has become available. Genetic risk assessment is a dynamic process and can change if additional relatives are diagnosed with cancer.

Types of Results

True positive means that a mutation has been identified that increases the risk of developing a cancer. A positive mutation cannot predict when or if the disease will actually happen.

True negative means that the individual has not inherited the mutation. The person has as much risk as the average person to develop a cancer.

Variant of unknown significance (VUS) means that the test detected a change, but it is not yet known if it is a harmful change.

What Is My Risk?

According to the NCCN, the goal of genetic counseling is to empower the person to make educated, informed decisions about genetic testing, cancer screening, and cancer prevention. Elements that increase the risk of developing breast cancer include family history, advancing age, ethnicity/race, breast density, and lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, obesity, and prolonged use of hormones.

Risk-reducing behaviors focus on maintaining a healthy lifestyle, such as exercising, maintaining an optimum weight, and quitting smoking. Those with positive results should talk with their HCP about reducing their risk specifically. Those with positive results could be eligible to have a risk-reducing surgery, either bilateral mastectomies (removal of both breasts) or hysterectomy with salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the uterus and ovaries). Although this helps to reduce risk, it does not eliminate the risk for cancer. Certain people can take specific medications provided by a medical oncologist to help reduce the risk of some cancers.

Now That I Have Been Tested, What’s Next?

Posttest counseling should be done by a licensed or certified genetic counselor and includes disclosure of the results, as well as a discussion regarding the significance of the results along with medical management options and follow-up care. If a variant is discovered, discussion with other potentially affected family members may be indicated. Posttest counseling should include providing information regarding resources, such as disease-specific support groups, advocacy groups, and research studies if available.

A genetic risk team should include the HCP, the gynecologist (if female), the genetic counselor, and an oncology nurse. There is not necessarily a need to include a medical oncologist or surgeon unless risk-

reducing medication has been chosen. All members of the team should have a copy of the test results and the individual’s plan for how to reduce risk.

The nursing profession has long been recognized as the most trusted profession because nurses are always on the front line of healthcare. Nurses establish relationships with our patients during daily interactions with them while assessing, treating, educating, and monitoring. As new research becomes available, updated methods of cancer screening, detection, and prevention may be determined. It is a nurse’s duty to stay abreast of this growing field so that we can educate our patients and their families on what to expect.

The healthcare team can help the affected mitigate their risk for cancer and can also help with the psychological effects of having a positive mutation or a VUS result. A VUS result can change in the future depending on what more we learn about those specific variants. It can weigh as a stressor on the mind of someone who knows they have a genetic mutation.

Talk with your HCP about the specific monitoring needs for colonoscopy, prostate exams and prostate-specific antigen labs, breast mammography, and gynecologic ultrasounds and exams. Most frequently, with positive mutations, these tests should be more frequent than for the general population. If results are positive, and it is decided at the time not to have risk-reducing surgery, the decision to have surgery could be made in the future—there is no set timeline for the surgery. This is especially helpful if monitoring fatigue occurs. This type of fatigue is most commonly reported in people who worry about the results with every test. This can cause stress that can only be resolved with being more proactive in the care plan. A nurse can help have this conversation with providers and can also help with learning some stress-reducing techniques, such as mindful meditation, distraction, or verbal counseling and consulting.

Some mutations have no surgical interventions, making increased screening the standard of care—seeing a dermatologist for skin monitoring for melanoma, the HCP for baseline neurological exams to have on file for potential neurological tumors, the HCP or gynecologist for breast exams and mammograms, gastrointestinal providers for colonoscopy, and other specific screening depending on the specific mutations. Cancers found early are typically easier to treat than those that are more advanced, and patients have better outcomes.

There are also support groups for those genetic predispositions. Facing Our Risk for Cancer Empowered is an international group that has support groups scattered throughout the United States, a national conference focused on those with mutations, and online education with the latest information for those interested. There may be other local support groups that can be attended as well. The important thing to remember is that those affected are not alone.

In summary, if cancer runs in the family, talk with an HCP, see a genetic provider who can evaluate your genetic risk, and get tested to know if there is a mutation. We can decrease our risk for cancer in several ways, but inherited genetic mutations cannot be changed. For those who do have a mutation, there are options to monitor for cancer more frequently, as well as surgical options, and plans for treatment options today can be changed in the future. Genetic mutations change the risk for cancer but do not necessarily mean a diagnosis in the future. Those affected are not alone, and the more we learn about mutations, the more precisely specific healthcare needs can be addressed.

References

- Mahon SM. Genetics. In: Watson JL, ed. Your Guide to Cancer Prevention. 1st ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2018.

- Myriad Laboratories. BRACAnalysis. https://myriad.com/products-services/hereditary-cancers/bracanalysis. Accessed February 11, 2020.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Hereditary Cancer Testing Criteria for High-penetrance Breast and/or Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Genes. Version 1.2020. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf.